|

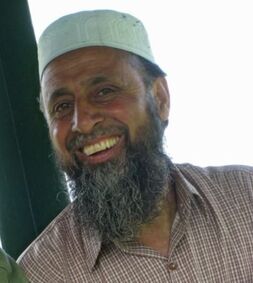

Mr. Abdul Rahman Mir, a retired forest guard from Jammu and Kashmir’s Dachigam National Park, was interviewed by YNN members Ekadh Ranganathan and Aditya Ramakrishnan as part of our World Ranger Day initiative, “In Nature’s Defence”.

With a deep love for the wild, Abdul worked for the forests of Dachigam with immense dedication as part of the Jammu & Kashmir Department of Wildlife Protection for several years. He was awarded the “Wildlife Service Award” by Sanctuary Asia in 2004 for his work towards conservation. |

As a child, I often used to visit Dachigam and other nearby conservation reserves. Since my father and grandfather worked in the Department of Wildlife Protection, there was always a passion for wildlife etched in me and I had an innate drive to serve and protect our wildlife. Dachigam is one of Kashmir’s most unique and fascinating landscapes and I always knew that I wanted to protect its beautiful flora and fauna.

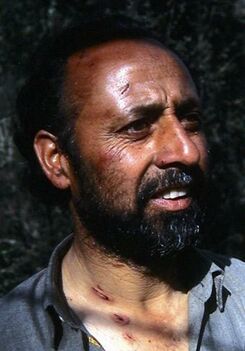

My favourite thing about my job was patrolling inside the park. I used to keep a lookout for Hangul stags, which were much rarer when I used to work, and even though there was no mobile signal inside the park, I would roam around it for weeks on end before returning home. I simply loved being inside the reserve, around nature, and always felt like protecting our biodiversity. Working in the park has left me with many fond memories too. Joanna Van Gruisen, a wildlife filmmaker, used to come to Dachigam quite often and I used to guide her around the park. Once, a Himalayan Black Bear attacked Joanna while we were on the trail. The bear was aggressive because it had two cubs with it, but I knew I had to risk my life to save everyone so I stepped in and fought the bear unarmed. This encounter left my body bruised and injured, but Joanna was untouched and we all returned alive. In fact, Mr. Bittu Sahgal, the founder of Sanctuary Asia, invited me to Mumbai to receive the “Wildlife Service Award” from Sanctuary Asia in appreciation of my response to the situation and all my conservation efforts at Dachigam. This remains one of my most favourite memories to this day.

As much as I loved my job, the tense political situation in Kashmir was a major problem. With the rise of militancy in the 1990s, a period when I did a lot of work, armed forces started patrolling inside Dachigam a lot more; something that adversely affected both the rangers and the animals. The situation was particularly bad in Upper Dachigam where animal movement is still very high, but is unfortunately an army patrolling hotspot. I’ve been chased many times by the army while doing my job and have even been stopped while trying to enter Upper Dachigam. Despite these challenges, other department staff and I were keen on protecting our wildlife and we continued to check on the status of the flora and fauna inside the park. Earlier, we used to feel comfortable patrolling alone in the forest but after the political change, we started to venture out only in groups of 3 or 4. Unfortunately, this situation persists even today. It is ironic that the main fear is not of the animals, but of the people. Bittu Sahgal was a great friend of mine even at that time and he would regularly call or visit and offer words of inspiration, saying we should never give up on the work we were doing. We continue to be in touch to this day as he has asked me to be a part of the COCOON Conservancy Project in Dara Conservation Reserve.

Climate change has also affected a lot of our wildlife adversely. Two of the most noticeable changes are in the behaviour of the Himalayan Black bear and the Hangul. Normally, the bears start hibernating in November but hibernation periods have been thrown out of sync due to early springs here. Sometimes, it doesn’t even snow in November causing the bears to start hibernating later than usual, shortening their overall hibernation periods. In the same way, Hangul spend much of their summers in alpine areas like Upper Dachigam but due to sudden drops in temperature and bouts of rainfall, they’ve stopped moving to higher slopes. Their habitats are greatly disturbed because of temperature fluctuation and years without snow, and our sightings of them have reduced drastically over the years.

Dachigam has changed a lot since I first started working there and not all for the better. When I joined, there were many dedicated workers who genuinely cared about conservation. Today, many positions have been left vacant and the officers aren’t as keen on protecting the landscape and its wildlife as their predecessors were. The message about conserving our ecosystems is no longer being passed down effectively and few people are properly trained or equipped with the knowledge required to preserve a whole ecosystem. But a major positive for me is that those living on the outskirts of the park are becoming more interested in sighting bears and stags and are starting to care more about nature overall.

Not a lot of people know about Dachigam’s unique biodiversity or landscape and I feel the media can play a great role in changing this. Back in my time, we didn’t have social media and not too many houses had landline phones either. We used to get a little publicity because people like Joanna and Ashish used to visit and film the wildlife found here. In this era however, more people can come to document our wildlife. I truly believe there is no place on Earth like Dachigam and if people come to document it, naturalists and conservationists will be even more inspired to protect the wildlife here.

Today, we must concentrate a lot of our energy on effectively delivering our ideas about conservation to as many people as possible. More training must be imparted; schools, colleges and universities should have separate courses about conservation and all that goes into it. To inspire future generations to do their part, we need to start talking about the stories of our forefathers, who risked their lives to protect our wild spaces.

My final message, especially to those living in cities, is about coexistence. Co-existence is incredibly important for conservation, especially in terms of the resources we get from woodlands and rivers. By teaching people about the importance of these resources to both us and wildlife, we can teach them how to live in harmony with nature. In fact, the very idea behind making Dachigam a conservation reserve was to protect a key resource- water from the Dagwan River, which flows through the reserve. This is the main source of water for Srinagar and forms most of the water in the Dal Lake. By educating more people about the importance of forests in terms of the essential resources they provide, we can teach them to value our biodiversity more.

At the end of the day, nature has made humans, wildlife and forests such that they are always in balance with each other. This coexistence between man and wild is the main idea we need to convey to those living outside forests.

At the end of the day, nature has made humans, wildlife and forests such that they are always in balance with each other. This coexistence between man and wild is the main idea we need to convey to those living outside forests.

We would like to thank Mr. Kashif Farooq for helping us translate Mr. Abdul’s words into English. Mr. Kashif is from Srinagar, Kashmir. He is currently pursuing a bachelor's in Agriculture from Integral University, Lucknow. He is also a wildlife photographer and writer focusing on wildlife, forests, conservation and conflict issues. He attributes a lot of his interests to his father, his paternal and maternal grandfathers and his great grandfather who all served in the Department of Wildlife Protection. He aims to join the same department and follow the footsteps of his father and grandfather to make Dachigam National Park a fine habitat free from all kinds of disturbances and threats to wildlife.

We would also like to thank Sanctuary Asia's Mud on Boots Project for their assistance in contacting Mr. Abdul for this initiative.